In this episode, we focus on Malinche, the interpreter for Hernán Cortés. In an interview with Laura Esquivel, the author of Malinche (2006), she shares her insight into Malinche’s perspective, and her reinterpretation of the figure of Malinche as a Mexican herself. This interview was translated in real time by Jordi Castells, who is also the illustrator for the codex images in Malinche.

You can get Malinche from Amazon here.

Malinche: A Broken Identity (2021) – A short film on Malinche by Lucille Lortel Theatre that “addresses the origins, names, life, and real and symbolic functions Malinche has performed throughout Mexican history”.

Malinchism – a perjorative that describes those who think that foreign values are superior.

Twitter thread from @AztecEmpire1520 on Cortes’ many mistresses

Further readings:

Aveling, Harry. ‘La Malinche, Laura Esquivel, and Translation’. Translation Review 72, no. 1 (September 2006): 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.2006.10523944.

Mukherjee, Indrani. ‘“Seeing” the Malinche Myth as Nomad Subject in Laura Esquivel’s Como Agua Para Chocolate’. Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics 43, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 51–63.

Tate, Julee. ‘La Malinche: The Shifting Legacy of a Transcultural Icon: The Latin Americanist, March 2017’. The Latin Americanist 61, no. 1 (March 2017): 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/tla.12102.

Townsend, Camilla. Malintzin’s Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. Diálogos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Transcriptions for the interview are available below, first in Spanish and then in English.

Transcribed by Ralph Manuel, in Spanish:

Me preguntaba porqué habías elegido escribir sobre Malinche. Leí en una de sus entrevistas sobre otro libro que publicaste que la editorial en españa te hablo sobre escribir sobre ella.

L: Por supuesto, Malinche es una figura muy presente en nuestra historia nacional. Y tradicionalmente nos enseñaban en los libros en la escuela, es que ella era una traidora o en el mejor de los casos una colaboradora con los españoles para derrocar el imperio azteca. La verdad, Malinche es la única novela que yo he escrito por encargo, pero cuando ellos me buscaron y me dijeron que querían hacer una biografía novelada corta de Malinche. Por supuesto que dije que sí y me pregunté: “¿Cómo nunca me había ocurrido escribir sobre este personaje?.

Cuando empiezo a desarrollar esta biografía —voy a abordar otras de las preguntas, me voy a adelantar un poco—. Pero en el momento que empiezo a hacer la investigación histórica. Fui muy cuidadosa y muy estricta para ajustarme a la información que teníamos de ese momento histórico. Pero empiezo a descubrir inmediatamente que Malinche no era lo que a mi me habían contado.

Para empezar, para traicionar algo o alguien tú tienes que haber pertenecido a esa organización que has traicionado y este no era el caso. Ella pertenecía a un pueblo que estaba sojuzgado por el imperio azteca. Empezó a fascinarme la historia de esta mujer quien tiene que haber sido muy inteligente y brillante, porque ella no hablaba español y dicen que ella lo aprendió en tres meses. Debido a que en un inicio uno de los soldados de Cortés hablaba Maya. Cuando descubrieron que ella hablaba náhuatl, entonces la utilizaron para que les ayudará a traducir el maya al náhuatl a los enviados de Cor és.

Nada más hacer este ejercicio de triangulación, aprendió español. Nada más de memorizar lo que le había dicho Cortés en español al soldado que hablaba maya, ella fue aprendiendo y memorizando, lo cual te da una idea de la mente de Malinche. Además, su trabajo de traducción tiene que haber sido muy complejo porque el náhuatl, el maya también, pero el náhuatl sobre todo son un lenguaje simbólico. Lleno de poesía y de metáforas. Por ejemplo, para traducir la palabra Quetzalcóatl, tu no puedes decir que nada más significa ̈ serpiente que vuela ̈ ,porque atrás de esa imagen simbólica estaba encerrado un pensamiento cosmogónico. En este lenguaje cosmogónico, esta figura que vuela te habla de cómo tu dejas una condición terrenal para convertirte en un espíritu y volar.

Entonces, me empecé a sentir muy maravillada con eso y por otro lado durante la escritura tuve dos grandes retos. Uno, era que yo tenía la libertad de crear este personaje histórico libremente. Porque de ella en las crónicas de los españoles escritas durante la conquista, hay como mucho seis cuartillas. Entonces, yo podía realmente desarrollarla, pero tenía en contra que me tenía que ajustar a sucesos históricos. Eran como una faja, como un sostén. Entonces, me llevó tres años de investigación, leí muchos libros y tesis, pero también recorrí la tradición oral. Porque todavía en nuestros tiempos aún hay guardianes de tradición sagrada en este país. Con todo esto ya tenía material para sentarme a escribir sobre ella.

Se dice que uno nunca ve el mundo como es sino como uno es. Mi pregunta desde el inicio fue ¨¿Cómo era Malinche? ¿Qué pensaba? ¿Qué significaba para ella encender el fuego? ¿Qué significaba observar el cielo? ¿Qué significaba el grano de maíz para ella?. Tenía que ver con el profundo pensamiento espiritual que ella había heredado, que la hacía ver el mundo de una manera. Y me imaginó que cuando ella ve a los españoles quiere creer como todos los demás que ellos eran prueba de que Quetzalcóatl había regresado. Para mi la palabra clave durante toda la escritura fue la idea de Quetzalcóatl y lo que significaba, por que es el motivo del equívoco, pero también es el símbolo de la liberación. Entonces, para organizar mi material conté con la ayuda maravillosa de Jordi [el traductor]. Él es un gran diseñador gráfico entonces yo tenía todo esto que tenía que organizar y sintetizar porque se trataba de un libro corto.

Entonces lo que ocurrió es que ahora todos traemos en nuestro celular siempre las fotos que nos gustan y contamos nuestra historia a través de fotografías. Entonces dije: si ella hubiera contado su propia historia, ella lo hubiera hecho a través de imágenes. Porque en la cultura de nuestros ancestros, la forma que se guardaba el conocimiento era a través de imágenes escritas en códices que se guardaban la memoria.

¿Qué tan grande fue el papel jugaste en la ilustración de los códices?

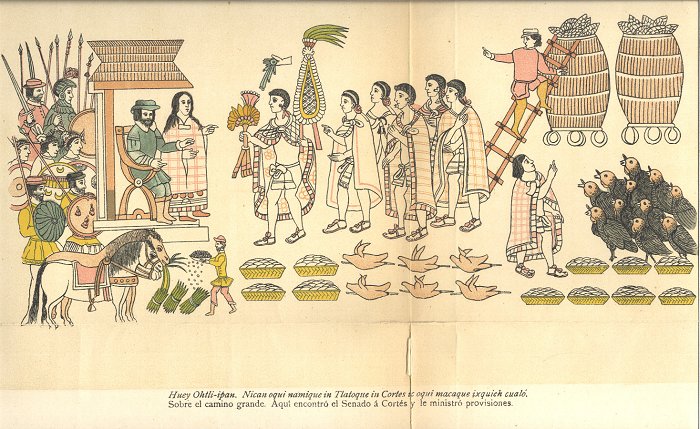

Jordi, el Diseñador: No era difícil, era un placer. Laura me dijo: si Malinche contaría su historia, dibujaría un códice. Entonces creamos todo el códice de su vida. Para cada capítulo leí el texto de Laura, encontré las partes más importantes y dibujé un pictógrafo. Fue un proceso meticuloso de investigación! Ver todos los códices reales y encontrar todos los símbolos correctos para las palabras, para los lugares. Usamos papel amate, que era el papel que usaban entonces y tinta china negra. Porque no pude encontrar las tintas que usaban originalmente.

Intentamos que pareciera tan auténtico y real, como algo que se hubiese encontrado en esos tiempos. [Mostrando los códices] Este es Malinche y Jaramillo —el hombre con el que se casara—. Este [Mostrando los códices] es de ella y Moctezuma y este es el símbolo de Quetzalcóatl. Quetzalcóatl está siempre presente con ella, él tiene su propio símbolo —la concha de mar—, este símbolo está representado en todas las imágenes.

L: Entonces, yo le decía a Jordi: en este capítulo quiero empezar de cuando nació, y él lo ilustraba. Esa fue, para mi, una forma maravillosa de para poder ir dando forma a la historia contada desde el punto de vista de Malinche.

¿Cómo decidiste cuánto de tu investigación histórica incluir en la novela contra cuánta licencia creativa tomar ?

L: Me apegue lo más que pude a lo histórico, pero al mismo tiempo — y ese fué el gran reto— desarrollar una historia de Malinche que no está registrada, pero basada en el pensamiento de esa época y en los hechos históricos. Por ejemplo, para mi era muy importante mostrar porque era importante la presencia de una deidad femenina. Porque en la tradición prehispánica todas las deidades tienen una representación masculina y femenina. Esta presencia, este juego de lo masculino y lo femenino es lo que genera la vida y lo que da juego al universo entero.

Por ejemplo, cuando Cortés viene, trae consigo la imagen de la Virgen de Guadalupe desde España. Ese punto para mi es importantísimo porque ahí ella [Malinche] empieza a cuestionar. ¿Dónde está la presencia femenina? y ¿Por qué no aparece como parte de la historia de Jesús, que les vienen a imponer?

Yo desarrollo en la novela todo un abanico de lo sagrado femenino. Empezando por esta presencia de Cihuacōātl, la gran madre. Durante toda la historia yo muestro como hay una presencia que empieza en Cihuacōātl y se va transformada hasta llegar a la Virgen de Guadalupe, donde Malinche está incluida.

El nombre de ella no era Malinche. Su nombre original era Malinalli y el glifo del día que ella nació es un cráneo que tiene la yerba “malinalli”. Esto significa: todo muere para renacer nuevamente. Y ese es el nombre de ella. Ella representa todo eso que va a morir para renacer. Empezando por el lenguaje, ella es la lengua de Cortés. Yo voy creando la importancia de esta lengua que habla y que traduce y que convierte que es la que empieza a convertir y unificar dos pensamientos totalmente dispares.

Entonces, nunca tuve la idea glorificarla, sino únicamente de ponerla en su justa dimensión. En la novela yo juego con esta idea de que todo el tiempo ella tiene que enfrentar su propio sistema de pensamiento y lo tiene que ir cambiando. Por ejemplo, en un inicio yo creo que ella si cree que los españoles vienen en representación de Quetzalcóatl, pero inmediatamente después se tiene que haber dado cuenta de que no era así, pero ya no había vuelta atrás. Porque el rectificar significaba su propia muerte.

¿Describirías la relación entre Cortés y Malinalli como una metáfora para la relación entre el colonizador y colonizado? Dado que al principio, ella estaba encantada por Cortés, ¿pero después de la masacre de Cholula se da cuenta que eran salvajes y violentos? ¿Cómo describes la relación entre ambos? Y ¿Fue esta una metáfora sobre la colonización?

L: No era una metáfora en verdad ellos tuvieron una relación intensa. Creo que ella fue tan importante para él que él buscó la forma dentro de su sistema de pensamiento y su cultura de dejarla en una buena posición. Él nunca se iba a casar con ella. Él era un hombre muy ambicioso y lo que quería a través de la conquista era ser el gran gobernador de México. Incluso independizarse de los españoles. Para eso, él necesitaba casarse con una mujer española que le diera importancia. Él lo que hace como su forma de darle un mejor destino a ella es casarla con uno de sus capitanes. Aunque no fue una unión muy afortunada y una vez más Malinche estuvo en una posición subordinada. Hasta que encuentra finalmente en Jaramillo una pareja que la valora y con la puede establecer una relación. Entonces, justo antes del final yo pongo como ella se va convirtiendo ella misma en Quetzalcóatl.

Quetzalcóatl que era una deidad fue engañado por su hermano con un espejo negro. Hernán Cortés para Malinche fue ese espejo negro y ella se lo reclama justo antes del final. Le reclama que lo peor que le ha pasado a ella es haberse mirado a ella misma en ese espejo negro que es Cortés. Como Quetzalcóatl, en la forma en que la serpiente se eleva y se convierte en una estrella de luz —de acuerdo a la tradicion— ella hace toda una recapitulación de su vida, confronta sus espejos negros que la remiten a una imagen que ella no es y en ese momento ella transmuta y se convierte allí en el patio de su casa en el centro de los cuatros puntos cardinales y se convierte en luz. Así es como yo termino la historia.

Para mí, escribir su historia fue toda una manera de dignificar mi propio pasado histórico. Porque para los mexicanos a nivel inconsciente ella representa la madre y Cortés el padre. A Cortés se le considera un asesino y un ladrón y a ella una prostituta y una traidora. Si nosotros somos hijos que descendemos de esa unión, no somos muy merecedores de vivir en paz, ser respetados, ser reconocidos. Creo que Octavio Paz, uno de nuestros grandes escritores, lo plasmó uno de sus libros “Laberinto de la Soledad”. Él explica que este fenómeno de sentirnos “hijos de la chingada”. Creo que estamos en ese proceso de re-dignificación, si nosotros pudiéramos tener una visión diferente tanto de Malinche como de Cortés y valorar ese momento histórico como un momento de unión Porque realmente con los españoles había herencias africanas, chinas, árabes, venía sangre de todos ellos mezclada en las personas que nos conquistaron. Y aquí en verdad es un vientre en donde se mezcla todo esto y nace una nueva raza y yo me siento muy orgullosa de ello.

¿Cómo fue la recepción de su libro en México e internacionalmente? ¿La gente te dice que cambiaste su opinión sobre Malinche y la conquista?

L: Sí, la verdad la gente le agrado mucho esta nueva visión e incluso ya ahora hay muchísimos artículos, hay muchísimos historiadores que han revalorizado la presencia de Malinche (no solo por mi libro). Y a manera internacional también es un personaje que interesó mucho en ciertos países mas que en otros por ejemplo en Alemania, España, e Italia. A mi me da mucho gusto porque creo que de eso trata. Cuando uno revisa el pasado, la idea no es nada más juzgar o analizar desde el presente. Tenemos que colocarnos en este momento histórico y allí es cuando puede comprender en toda la extensión de la palabra. Al estar en los pies de esas personas es cuando uno puede comprender su actuar.

Transcription in English:

Why did you choose to write about the figure of Malinche? I read in another interview that the publishing house in Spain suggested the figure of Malinche. I was wondering if you had any other motivations for writing about Malinche?

Of course, Malinche is an essential figure in our national history. Traditionally, what we are taught about in school as children is that she was a traitor, or in the best of cases, a collaborator with the Spaniards to overthrow the Aztec empire. Malinche is the only novel that I’ve written by request of a publisher. When this publisher sought me out and told me they wanted a short novelised biography of Malinche, I immediately agreed and wondered why I had never thought about writing about this character myself. When I started doing my historical research, I was very careful and very strict to stick to the information we have from that time period only. And I started to discover immediately that Malinche wasn’t this person that I had been told about. For starters, to become a traitor to somebody, that would mean you had to belong to that group or to that institution, and that was not the case with her.

She belonged to a culture that was under the Aztecs’ rule, or a tributary state of the Aztecs. I became fascinated with the story of this woman who had to have been very brilliant and smart, because she obviously didn’t speak Spanish. It’s been said that in three months, she was fluent in Spanish. The connection was that one of Cortes’ soldiers spoke Maya, and when they discovered she spoke Nahuatl, they used her to translate from Maya to Nahuatl when they communicated with Cortes’ envoys. And from that triangulation, she taught herself Spanish. Just after memorising what Cortes said to the Maya speaker in Spanish, she learnt and memorised Spanish, which gives you an idea of how bright her mind was. Her job as a translator had to be very complicated, because Maya and Nahuatl are very symbolic languages filled with poetry and metaphors. For example, for the translation of the word ‘Quetzacoatl’, you can’t say that the only meaning is a flying snake, because behind that symbolic image of a flying snake was this entire breadth, this worldview of the cosmos that they had. This worldview and language that talks about this flying snake expresses how one can put aside their earthly condition in order to become a spirit and be able to fly. I was amazed by that.

When I started writing, I had two big challenges. One of the big challenges was that I had to create this historical character because in the information that I had from the time that the Spaniards wrote in their chronicles of the conquest, there was very little information about her. At most, there were six pages that mentioned her. I could really develop her as a character but I also had to respect the historical events that had happened. It felt like a corset squeezing me, forcing me to fit into that storyline. It took me three years of research, reading many books and historical theses and papers, but I also had access to oral traditions. Because to this day in Mexico, we have guardians of sacred traditions. With all of this, I finally had enough material to sit down and start writing about her.

People say that we never see the world as it is, we see the world as we think it is. And my question from the beginning was: What was she like? What did she think? What meaning was behind lighting a fire for her? What was the meaning behind watching the sky? What was the meaning behind a kernel of corn for her? It had to have been the profound spiritual beliefs that she had inherited that led her to see the world in a certain way. I imagined that when she saw the Spaniards, she wanted to believe like many others, that they were proof that Quetzacoatl had returned. For me, the key to make this all fit together in my writing was that image, Quetzacoatl, and what it meant. That’s the motive behind the mistake but it’s also a symbol of liberation.

In order to organise the material, I had help from Jordi. He is a graphic designer and illustrator. I had all this information to organise and synthesise because I was asked to write a short book. We all have our smartphones, we all keep our pictures there of what we like. We have our own stories that we tell through pictures. So I thought that if she was able to tell her own story, she would have done it through images. In our ancestors’ cultures, how they kept and transferred knowledge was through codexes, a pictographic language, and that is how they preserved memories.

How much of a role did you play in the illustration of the codexes?

Laura: Let me show you — let him tell you how difficult his job was.

Jordi: It wasn’t difficult, it was a joy. So Laura said, if Malinche could tell her story, she would write/draw a codex. We created the entire codex of her life. For every chapter, I went through and read Laura’s text and found the most important parts of each chapter and I made a pictographic illustration. This very first one is the birth of Malinche. That was a very painstaking work of research. It’s so much research looking at all the codices and finding the right symbols for the words, for the places. We did it on amate paper, which is the paper that they used back then, and just black india ink. I wasn’t able to find the pigments that they used originally. We tried to make it look as authentic and real [as possible], like something found from that time. (shows image) This is Malinche and the guy she marries, Jaramillo. (another image) This is a great one, this is her and Moctezuma. That’s Quetzacoatl. Quetzacoatl is ever-present with her, his distinctive symbol is a seashell. This symbol is always represented throughout the images.

Laura: These are the big moments in each chapter. So the first chapter, I would start with her birth, and then do the research, find depictions of births in codices and try to make something new but it also felt very authentic. That was a wonderful tool for me to be able to tell this story from her perspective.

For your historical research, how did you decide how much to include in your novel and how much creative license you would take?

I really stuck as much as I could to the historical events. That was a challenge to develop the story of Malinche – a story that had not been told – but based on historical events and whatever recollections we have of that time. For example, for me it was very important to explain why the presence of a female deity was very important. In the prehispanic tradition, every deity had a male version and a female version. This interaction between the masculine and the feminine is what gives life to the entire universe. For example, when Cortes comes, he brings with him an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe from Spain. That was very important for me, because then she starts wondering: in the religion that is imposed on them, where is the female version of Jesus?

(shows image) In the novel, I developed this whole storyline of the female sacred starting with Cihuacoatl, the great mother. In the story, I create this thread that starts with Cihuacoatl, this prehispanic goddess, and starts transforming into the version that we know of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico, and Malinche participates in that. Her name was not Malinche. Her name was Malinalli. The glyph for the date of her birthday is a skull that has the weed named Malinalli [atop]. Its meaning is that everything dies in order to be reborn. That’s her name. She represents everything that needs to die in order to be reborn, starting with language. She is Cortes’ tongue. She has this tongue that begins to speak and translate, and starts becoming the union of these two cultures and ways of thought that are completely different. It wasn’t my intention to glorify her, I just wanted to do her justice. (shows image) This is the glyph of her birth date. In this book, I talk about how she has to confront her own beliefs. For example, at first I think she was sure that the Spaniards were the envoys of Quetzacoatl. But she has to have realised quickly that it wasn’t true, but she couldn’t go back because changing her mind meant she was killing herself basically.

Would you describe the relationship between Cortes and Malinalli as a metaphor for the relationship between the coloniser and the colonised? Malinalli was at first entranced by Cortes, but after the massacre at Cholula and the Alvarado massacre, she realises that they were savage and violent. Why did you depict the relationship between Cortes and Malinalli this way, and was it a metaphor that you intended?

No, I don’t think that I intended it as a metaphor. They really had a very intense relationship. I think that she was important enough to him that he tried to find a way within his structure of beliefs and his culture to leave her in a good position. He was never going to marry her. He was very ambitious. What he wanted from the conquest was to be the ruler of Mexico, even independent of the Spanish Crown. In order to get to that point, he had to have a Spanish wife to be in the good graces of Spanish society. His way of giving her a good life and a good standing was to marry her to one of his captains. It wasn’t the best of marriages, and once more Malinche found herself in a subordinate position until with Jaramillo, where she eventually finds a partner that values her and with whom she can establish a relationship. Right before the end, what I intend is to explain how she herself becomes Quetzacoatl. Quetzacoatl in mythology was fooled by his own brother through the use of a black obsidian mirror. Hernan Cortes, for Malinche, was that black mirror and she tells him so. At the end of it, she tells him: the worst thing that’s ever happened to me is to see myself reflected in your black mirror. Like Quetzacoatl, the way that the snake can leave the earth and fly up to the heavens and become, like in tradition, a star, she does this entire summation/recapitulation of her life. She confronts her black mirrors that were showing her an image that was not her and that is when she transmutates in her home and becomes light. That is how I wrap up her story.

For me, writing her story was also a way for me to dignify my past. On a very subconscious level for Mexicans, she represents the mother and Cortes the father. Cortes is thought of as a murderer and a thief, and she is a prostitute and a traitor. If we think that we are the children of that union between a murderer and a thief, and a prostitute and a traitor, what does that make us? It probably doesn’t make us people who are worthy of respect, worthy of living in peace, worthy of being seen and recognised. One of our great writers, Octavio Paz, speaks about that in his book, The Labyrinth of Solitude. He speaks of this phenomenon of feeling like we’re equal to La Chingada, which translates to son of the raped whore. We are in the process of that re-dignification. If we had a new way of looking at Malinche and Cortes, and value that historical moment as an union, because the Spaniards themselves had African blood, Arab blood, Asian blood, so the people who came to conquer the natives had blood from all over the world. Mexico is like a womb that is truly mixed, that is truly the birth of a new race. I feel very proud of being [Mexican].

What was the reception for your book, in Mexico and internationally? Have people told you that you’ve changed their impression of Malinche, and of the conquest?

Yes, people really like this new way of seeing Malinche. Now, there are many historians and intellectuals who are reevaluating Malinche and her presence. Not just because of my book, it’s something that has been happening. Internationally, it had an impact. There were people who were very interested in this character, some countries more than others. Germany, Spain and Italy, for example. It’s really amazing to me, I think it’s very important when you look back at your past, we should [not] only be judging and analysing from the present. We should place ourselves in that moment of history. That’s the way that you can truly understand why people acted the way they acted, by putting yourself in their place.